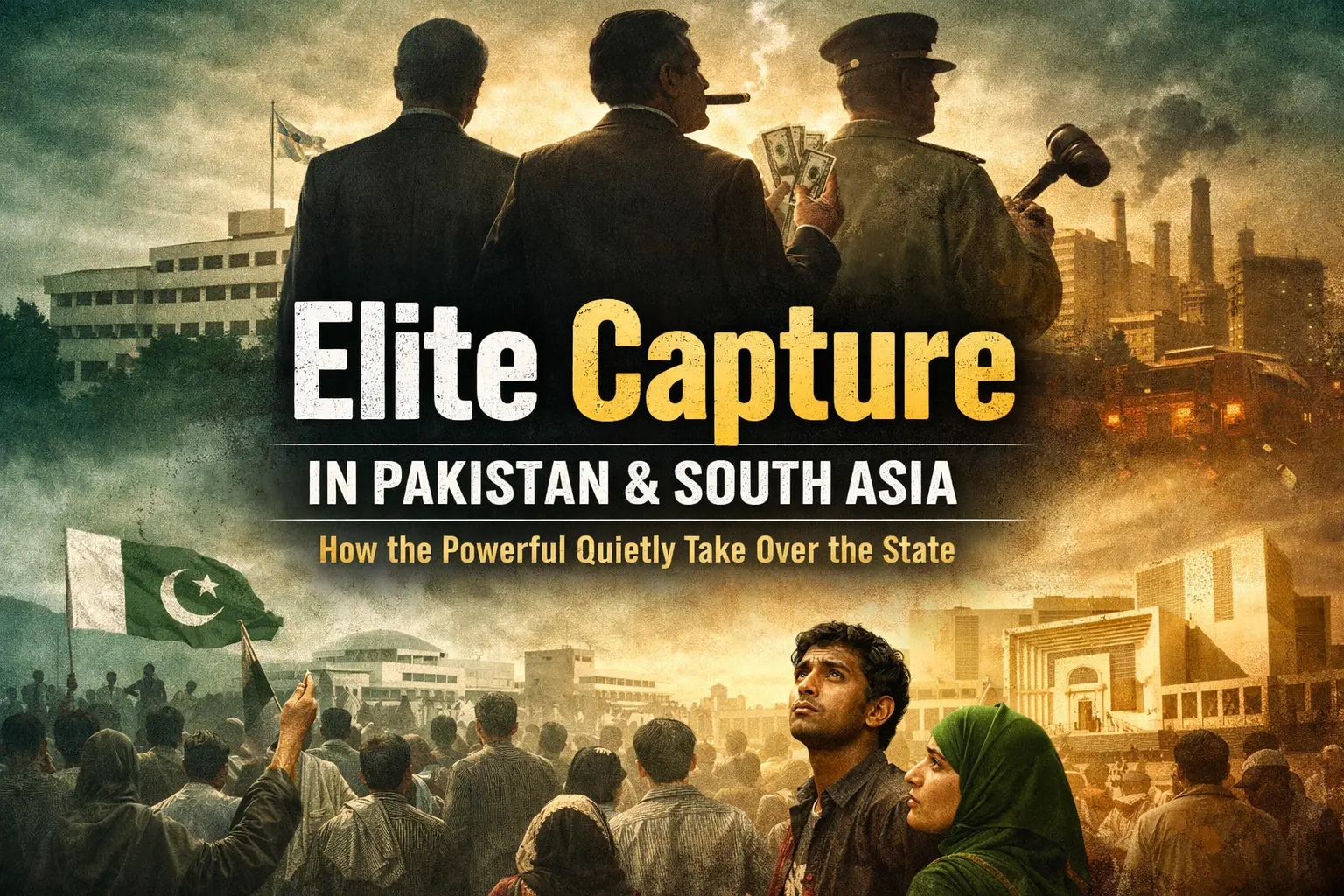

In Pakistan and across South Asia, the state has not collapsed. Flags still fly, institutions still function, elections are held, and laws are written. Yet for ordinary citizens, the experience of the state feels increasingly distant, unresponsive, and unequal.

Prices rise faster than incomes. Opportunities narrow. Justice feels selective. Each election brings hope, only to deliver the same frustration. This persistent gap between what the state promises and what people actually receive is not accidental. It is the result of a deeper and quieter process known as elite capture.

Elite capture occurs when a small, powerful group gradually takes control of state institutions, policies, and resources without dismantling them. The system remains intact, but its purpose shifts. Instead of serving the public, it begins to serve those who already hold power.

This is what makes elite capture so dangerous. It does not look like dictatorship or chaos. It looks like normal governance. By the time society recognizes it, elite capture has already become the operating system of the state.

What Elite Capture Really Means in Pakistan

Elite capture is often mistaken for corruption, but the two are not the same. Corruption breaks the rules for personal gain. Elite capture writes the rules so that only a few can benefit legally and consistently.

In Pakistan, power is concentrated within a narrow circle that includes political dynasties, economic cartels, entrenched bureaucratic networks, influential media groups, and selective accountability mechanisms. These actors may compete publicly, but they share a common interest behind the scenes: preserving privilege and resisting meaningful reform.

The state continues to function, but it no longer works for the majority. Governance becomes less about service and more about survival for those at the top.

Why Elections Rarely Bring Real Change

One of the most common questions Pakistani citizens ask is simple: Why does nothing really change after elections?

The answer lies in elite capture. Governments change, but the structure of power does not. Economic policies continue to protect the same sectors. The tax burden falls on the same groups. Accountability appears active, but stops just short of the truly influential.

Democracy becomes procedural rather than transformative. It produces governments, not structural change. The system absorbs political pressure without altering its foundations.

A Regional Pattern Across South Asia

Pakistan’s experience is not unique. Across South Asia, elite capture follows the same pattern while adapting to local conditions.

In some countries, political authority aligns closely with corporate power. In others, patronage shields economic elites from accountability. In extreme cases, elite mismanagement eventually overwhelms the state, producing economic or social collapse.

Different political systems, similar outcomes. The disease is regional, even if the symptoms vary.

The Civil–Military Dimension in Pakistan

Pakistan’s elite capture cannot be understood without acknowledging its civil–military history. Repeated failures by civilian elites to govern inclusively and transparently have created power vacuums that other institutions have filled.

While this has often prevented complete state breakdown, it has also delayed political evolution. Stability replaces reform. Control replaces accountability. Elite capture adapts rather than disappears, surviving under new power arrangements without ever being dismantled.

The state remains standing, but its long-term capacity to reform weakens further.

Economic Survival Without Development

Elite capture locks Pakistan into permanent survival mode. Economic planning focuses on managing crises rather than transforming productivity. External loans substitute for internal reform. Wealth accumulates at the top while the middle class shrinks.

Capital quietly leaves the country, and skilled professionals follow. Growth, when it occurs, is fragile and debt-driven. Development—the kind that expands opportunity and dignity—never fully arrives.

The economy moves, but it does not progress.

The Human and Psychological Cost

Beyond economics and politics, elite capture inflicts deep psychological damage. Over time, society internalizes the belief that effort matters less than access and merit matters less than connection.

Young people increasingly view emigration not as a choice, but as a necessity. Professionals disengage. Civic trust erodes. Patriotism weakens into resignation.

When citizens stop asking how to improve their country and begin asking how to escape it, elite capture has already achieved its most destructive victory.

Why Reforms Keep Failing

Every serious reform threatens someone powerful. Tax reform challenges privilege. Energy reform disrupts cartels. Accountability threatens gatekeepers. As a result, reform is rarely rejected outright—it is diluted, delayed, or reversed.

Committees are formed. Policies are announced. Roadmaps are published. But implementation remains partial and reversible. The system absorbs pressure without changing its shape.

This is how elite capture survives decade after decade.

Conclusion: A State Quietly Taken Over

Elite capture does not arrive as betrayal. It arrives disguised as experience, stability, and realism. It speaks the language of responsibility while practicing the politics of preservation.

Pakistan and many South Asian states are not failing because they lack institutions. They are failing because their institutions no longer serve the public interest.

Countries do not collapse when the state disappears.

They collapse when the state continues to exist—but quietly belongs to someone else.