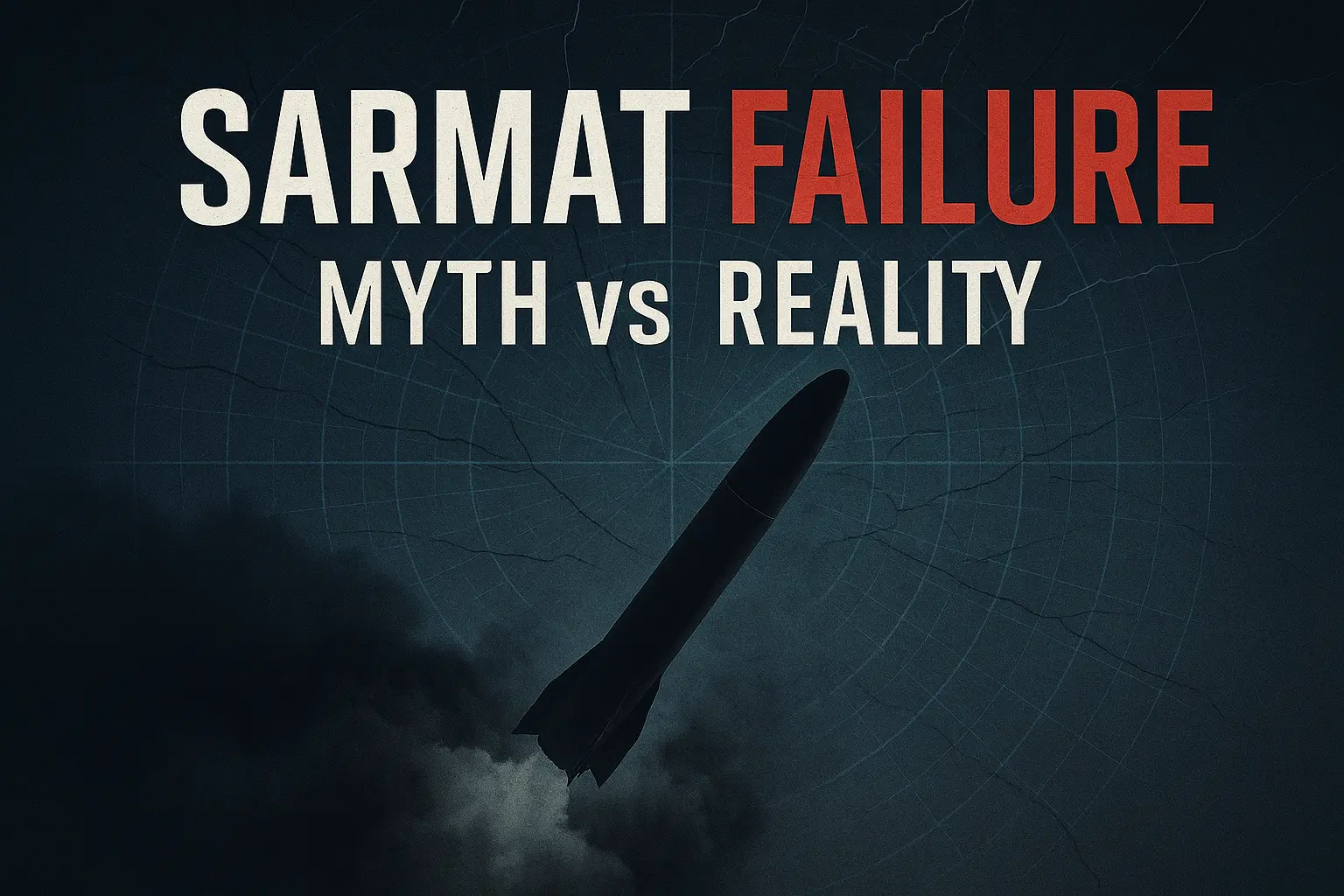

The RS-28 Sarmat intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) was never intended to be judged solely by its technical specifications. From the outset, it was designed as a psychological weapon — a system meant to shape perceptions, influence strategic calculations, and reinforce the idea that Russia’s nuclear deterrent remained not only intact, but untouchable. In official rhetoric, Sarmat was framed as inevitable, unstoppable, and decisive. Its very mention was meant to end debates.

That is precisely why the reported failure of a recent launch near the Yasny missile complex carries weight far beyond the test range.

Open-source footage showing a missile losing control moments after liftoff and detonating near the launch site struck at the core of Sarmat’s purpose. Moscow’s subsequent silence did little to contain the damage. In psychological warfare, absence of narrative control is itself a signal — one often interpreted as vulnerability. Whether officially acknowledged or not, the incident punctured the carefully constructed image of Sarmat as a mature, deployment-ready system.

Psychological deterrence relies on three pillars: capability, credibility, and consistency. Sarmat’s problem today is not capability on paper, but credibility in practice. For years, Russia used the missile as a strategic talking point, emphasizing its heavy payload, its ability to carry multiple warheads or hypersonic glide vehicles, and its alleged capacity to bypass Western missile defenses through unconventional trajectories. These claims were amplified deliberately, forming part of a broader information campaign aimed at NATO capitals.

However, psy-war is unforgiving. The higher the claim, the heavier the cost of visible failure. When a system marketed as “invincible” struggles to clear the launch phase, the psychological balance shifts. The audience — adversaries, partners, and domestic observers — begins to reassess not only the weapon, but the messenger.

The repeated delays and earlier test incidents associated with Sarmat have already weakened the narrative. A previous failure that reportedly damaged a launch silo raised serious questions within analytical circles, even if public discussion remained muted. The latest failure reinforces an emerging pattern: a weapon system announced as operational, yet still exhibiting characteristics of a troubled development program. In psy-war terms, this creates cognitive dissonance — a gap between declared reality and observable events.

From a psychological standpoint, Russia’s silence follows a familiar doctrine: deny adversaries confirmation, preserve ambiguity, and avoid public admission of weakness. Historically, this approach worked when information was tightly controlled. Today, it is far less effective. Satellite imagery, OSINT communities, and real-time video dissemination ensure that failures cannot be contained. Silence no longer creates uncertainty; it creates speculation, often in directions unfavorable to the originating power.

Crucially, the Sarmat incident does not undermine Russia’s nuclear deterrence in material terms. Deterrence is layered, redundant, and resilient. But psy-war is not about material balance alone. It is about belief. And belief erodes incrementally. No adversary needs Sarmat to fail completely; they only need to doubt its reliability, deployment scale, or readiness under stress.

Western defense establishments understand this distinction well. They are unlikely to treat the failure as a decisive blow. Instead, it will be logged as a data point — another indicator that Russia’s strategic modernization is under strain. In psychological terms, this reduces the coercive value of Russian signaling. Threats lose weight when the systems behind them appear uncertain.

There is also a domestic dimension. Strategic weapons are not only external signals; they are internal reassurance tools. They sustain public confidence in national strength during periods of economic pressure and prolonged conflict. When flagship programs stumble visibly, maintaining that confidence becomes harder. Over time, repeated discrepancies between official declarations and observable outcomes weaken trust in institutional messaging.

The broader psy-war lesson is clear. Strategic weapons programs that lean too heavily on propaganda invite disproportionate psychological damage when setbacks occur. True deterrence messaging is quiet, consistent, and backed by demonstrated performance. Loud declarations raise expectations — and failures then echo louder than successes.

In the end, the Sarmat episode is less about a missile and more about narrative erosion. Russia’s strategic forces remain formidable, but the myth of effortless technological dominance has taken a hit. In an era where perception travels faster than hardware, even a single visible failure can alter the psychological balance — not decisively, but cumulatively.

And in psychological warfare, cumulative doubt is often more powerful than any single weapon.